Paediatric poisoning in Kuwait-Al Adan joint hospital: The need for functional poisoning control centre in Kuwait

Affiliations

Affiliations

- Al Adan Hospital, Paediatric department, Ahmadi Medical Governorate, Kuwait.

- Faculty of Pharmacy, Kuwait University, Kuwait.

- Kuwait-Al Adan Joint Paediatric Hospital, Al-Adan Paediatric Pharmacy, Department of Pharmacy, Mohammad Tahous Nasser bin Tahous street, Sabah Alsalem 44001, Kuwait.

- Kuwait Hospital, Department of Pharmacy, Mohammad Tahous Nasser bin Tahous street, Sabah Alsalem 44001, Kuwait.

- St. George's University of London, Cranmer Terrace, Tooting, London SW17 0RE, UK.

Abstract

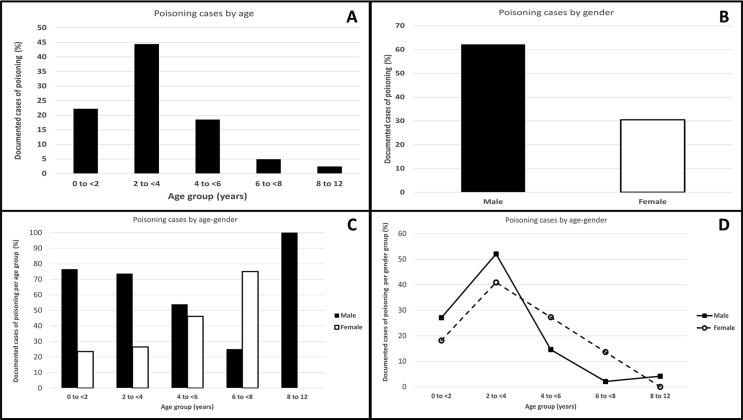

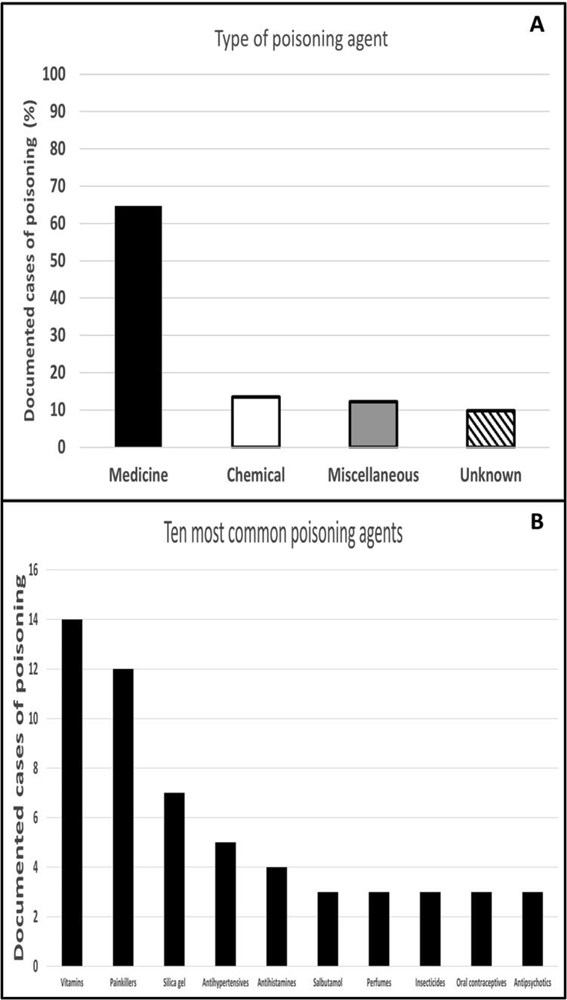

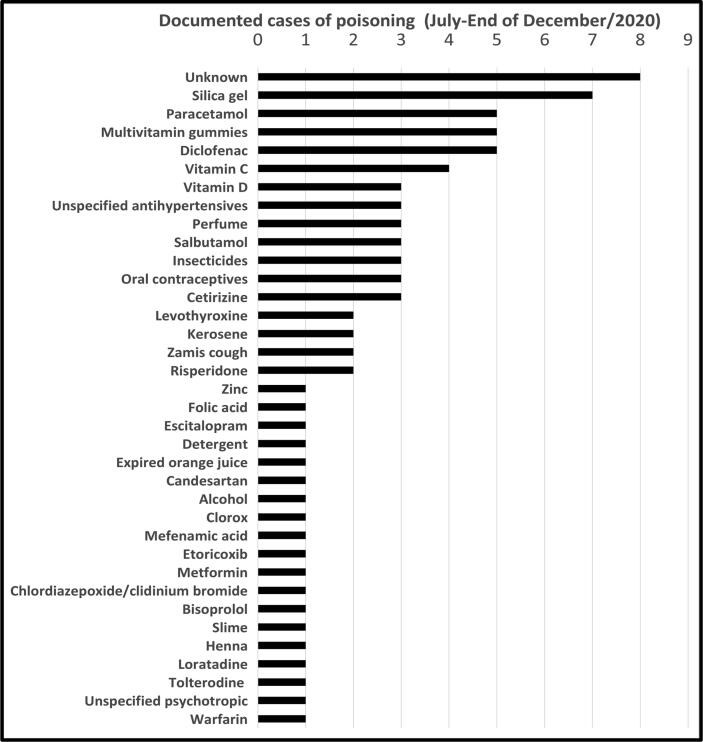

Poisoning is a major global health concern. Every year, unintentional poisoning contributes to 106,683 deaths globally. In Kuwait, paediatric poisoning cases comprise approximately 50% of total poisoning cases. Despite the extensive importance and the long history of poison control centres (PCCs) and the emphasis of the World Health Organization (WHO) to establish a PCC in Kuwait, no functional PCC exists in Kuwait. Here we reported 82 poisoning cases between July and December 2020, revealing a 100% increase in comparison to the official figures published in 2004 and 2005. No fatalities were reported, and all cases were discharged home within 12 h of their visit to the casualty. Children aged 2 to < 4 years comprised the most reported poisoning cases with approximately 45% of the total. The number of male child poisoning cases was approximately two-fold of female children. The most common poisoning agent was silica gel granules (9%) followed by medicines - reported as paracetamol (7%), diclofenac (7%), multivitamin gummies (7%) and vitamin C (5%). Among other causes of poisoning were ingestion of salbutamol nebulizer solution (4%), oral contraceptives and insecticides (4%). These findings reveal the importance of establishing a functional PCC in Kuwait to minimise the unnecessary visits following ingestion of expired orange juice and henna, that may encounter further contraction of infections, especially with the current state of the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, a functional PCC would provide comprehensive data and hence further intervention such as shifting the dosage form of salbutamol from nebulizer solution to metered dose inhaler with a spacer, in addition to increasing public awareness towards minimizing such a dramatic increase in casualty visits because of -suspected poisoning.

Keywords: Hospital; Kuwait; Paediatrics; Poison control centre; Poisoning; Toxicity.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Figures

Similar articles

Chan BS, Dawson AH, Buckley NA.Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2017 Feb;55(2):88-96. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2016.1271126.PMID: 28084171 Review.

Johnson AR, Tak CR, Anderson K, Dahl B, Smith C, Crouch BI.Am J Emerg Med. 2020 Aug;38(8):1554-1559. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.158418. Epub 2019 Aug 27.PMID: 31493977

Liakoni E, Berger F, Klukowska-Rötzler J, Kupferschmidt H, Haschke M, Exadaktylos AK.Swiss Med Wkly. 2019 Dec 17;149:w20164. doi: 10.4414/smw.2019.20164. eCollection 2019 Dec 16.PMID: 31846508

Outcomes of acute exploratory pediatric lithium ingestions.

Minhaj FS, Anderson BD, King JD, Leonard JB.Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2020 Sep;58(9):881-885. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2019.1704772. Epub 2020 Jan 8.PMID: 31913731

Woolf AD, Erdman AR, Nelson LS, Caravati EM, Cobaugh DJ, Booze LL, Wax PM, Manoguerra AS, Scharman EJ, Olson KR, Chyka PA, Christianson G, Troutman WG.Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2007;45(3):203-33. doi: 10.1080/15563650701226192.PMID: 17453872

KMEL References

References

-

- AbeerAl-mutawa E.A., Hedaya M., Koshy S. Intentional and Unintentional Drug Poisonings in Mubarak Al-Kabeer Hospital. Kuwait. J Pharma Care Health Sys. 2015;2(2376–0419):1000139. doi: 10.4172/2376-0419.1000139. - DOI

-

- Aziz N.F., Said I. The Trends and Influential Factors of Children's Use of Outdoor Environments: A review. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2012;38:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.03.341. - DOI

-

- World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean: 2014. Country Cooperation Strategy for WHO and Kuwait 2012–2016. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/113231 (Accessed 22 April 2021)

-

- World Health Organization Guidelines for Establishing a Poison Centre. 2020. https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/who-338657?lang=en Accessed 22 April 2021.